|

www.eclipse-chasers.com Solar Eclipse Weather Experiments Author: Jay Anderson Last update: Thursday, 29-Dec-2016 10:26:28 EST |

Eclipse Chaser

(noun) - Anyone that wants to see a total solar eclipse.  Search Eclipse Chasers Site

Search Eclipse Chasers Site |

Solar Eclipse Weather Experiments

- Jay Anderson

Local weather will change as a result of a solar eclipse. Because the energy from the Sun is being cut off by the Moon you will notice a drop in temperature as if the Sun had been hidden by a thick cloud. The change will be gradual over the course of the solar eclipse and will be notable in places where just a partial is visible. A total solar eclipse will result in the greatest weather data changes such as temperature and maybe even wind speed and cloud development. The following are some experiments you can perform during an eclipse of the Sun.

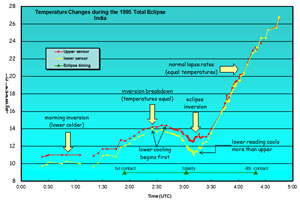

* Temperature drop – make sure thermometer is always in the shade during the course of the measurement; use two thermometers if you can, one low down (perhaps even on the ground), one higher up (that way you can see the growth of the surface inversion) – height doesn’t matter too much, but 1 ½ metres or more for the top one (or try several levels). Use a fast-response thermometer and ventilate it (with a fan) if you can. For proper science, you will have to determine and account for the instrument lag; with more than 1 thermometer: they have to be calibrated against each other (absolute temperature doesn’t matter much, but relative does).

| From the 1995 Eclipse | |

|

I placed the upper thermometer (a digital one from Radio Shack) on the top of a stick attached to my equipment case. It was shielded from the Sun by a small bit of cardboard - I had to make sure that it stayed in the shade and that it was suspended in the open. The lower thermometer was taped to the top of a beer bottle and in the shade of the equipment box. The temperature curves from the two sensors are shown in the graph. Because it was an early morning eclipse, the night inversion had barely dissipated before the eclipse cooling began and the inversion reformed. A the same time, I measured the UV light levels, but they aren't important for this experiment. The eclipse was only about 45 seconds long or something like that. (Click images for full size.) |

|

* Light level measurement - track the Sun if you can, otherwise a sensor that has a wide field of view and check that it is uniform. You can also measure the signal from a white card or other part of the scene as long as it is well exposed. You might try different wavelengths, but I don’t know what might come of it (I’ve done it in UV).

* Wind speed monitoring – must be well-exposed (the rule is 10 times the height of the sensor, but the sensor is usually 10-m off of the ground for the usual weather office measurement, which means you need a 100-m clearing). I’d go for more. Try several levels, as the wind speed near the ground should drop and its variability should decrease as the surface inversion builds. All directions are true, not magnetic.

Other ideas –

- Measure colour changes by photographing a white target at periodic intervals with a digital camera. Be sure to set the digital camera on manual settings, with no automatic corrections for light or colour balance.

- Set up a vertically pointing radar and measure changes in low-level turbulence (check with your local TV or radio weather reporters, they might have one and be interested).

- Try sky photographs with polarization filter (also corona), with different orientations. Watch and photograph (or video) the flash spectrum and coronal spectrum using a diffraction grating.

- Watch and record changes in cloud, cloud iridescence.

- Take a piece of cardboard and cut 5 eye-width slots in it. Leave the top slot clear. Put a solar filter in the second one. Put polarizing material in the third and fourth, at different orientations so that you can switch back and forth quickly to view coronal polarization. Put a diffraction grating in the bottom. Try to remember everything you see as you cycle through the view ports in the 8 seconds you will have available. (all eclipses are 8 seconds unless they are shorter).

Editor TIP: When doing manual recordings of the temperature or wind speed, do not try to multitask. Assign a team member to each task. In 1973 editor Bill Kramer (see photograph below) attempted to do too much at once - photography, observe, record temperature. I did manage to get two out of the three (no recorded temperatures).

The experiments suggested above come from Jay Anderson, meteorologist and eclipse expert. They are the result of direct questions asked on the Solar Eclipse Mailing List. The SEML is open to anyone with an interest in solar eclipses. Regular contributors include members of the international science community.

This is a work in progress! Suggestions and further information are welcomed.